Artificial Intelligence: a science in need of a conscience

It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out that artificial intelligence will be the great revolution of our century. AI stands at the crossroads of technology, ethics, morality, and the human factor. And that’s what makes it so fascinating. Several AI heavyweights, among them DeepMind, have already squarely placed ethics at the centre of their corporate culture, a reminder that science rhymes with conscience.

In a previous article about deep learning’s amazing applications, I wrote about DeepMind and its early successes. Back in the early 2010s, DeepMind developed an intelligent agent that taught itself to play various video games, quickly becoming unbeatable. Thanks to Deep Reinforcement Learning, the programme first learned the principles of the game through trial and error, then refined its technique in pursuit of the highest score possible. This strategy proved formidable for classic games like Breakout, Pong and Space Invaders.

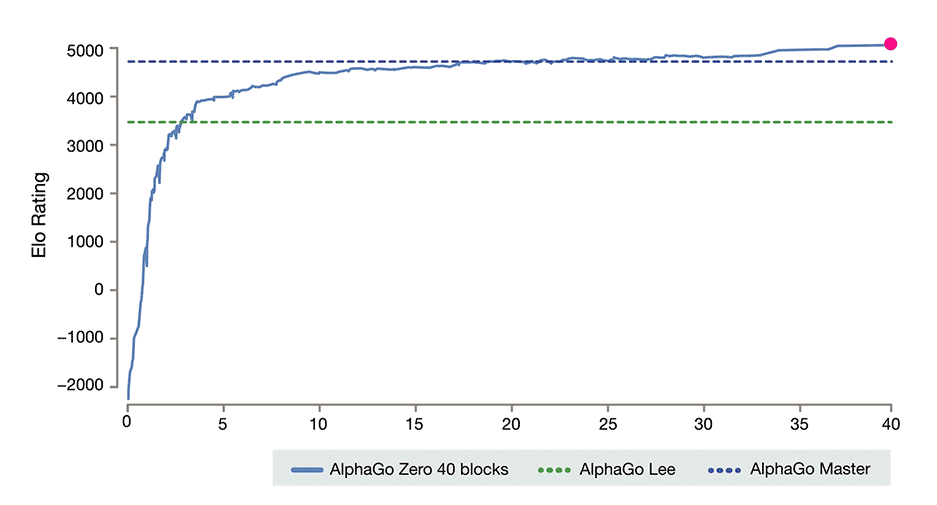

Since then, this British start-up has become a large corporation and a major international player in artificial intelligence. Bought out by Google/Alphabet in 2014 for over 500 million dollars, it has augmented its headquarters in London, England with offices in Mountain View, California, and Edmonton and Montreal in Canada. The master of Breakout has evolved into AlphaGo Zero, a programme able to master more complex games, including Go, chess and Shogi, in a matter of hours. The programme learns just by playing against itself, doing away with the lengthy process of digesting a database of games previously played by humans. In fact, AlphaGo Zero has surpassed its previous iteration, AlphaGo Lee, which had beaten world champions Lee Sedol and Ke Jie, thus probably becoming the all-time world champion of Go.

Progress of AlphaGo Zero’s Elo ranking in 40 days, compared to the best rankings of the previous versions, Lee and Master. © DeepMind.

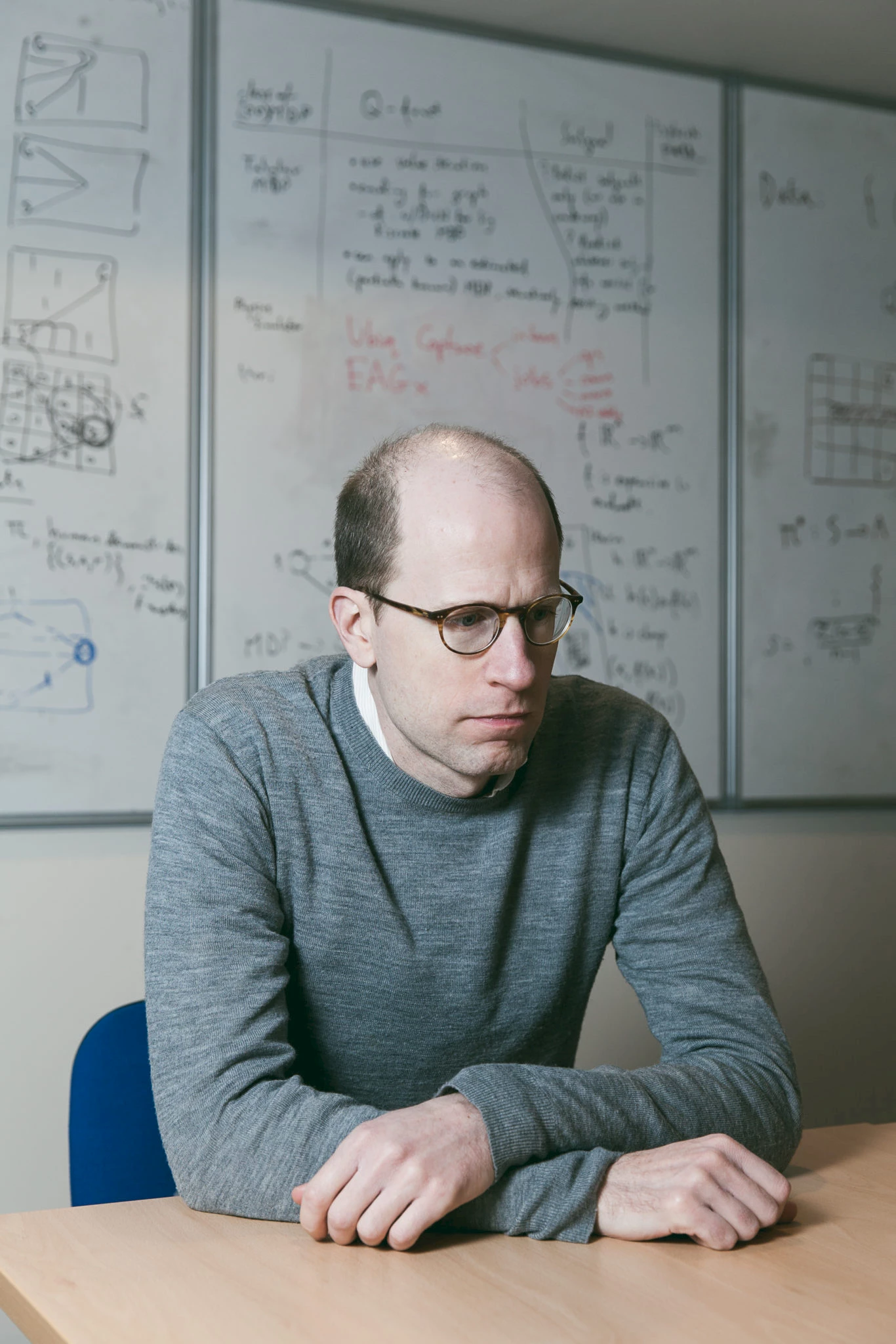

An interesting aspect of the 2014 transaction is that DeepMind’s acquisition by Google was conditional on the creation of a safety and ethics committee whose mandate would include the oversight of technology transfers between the two companies. Indeed, the issues of morality and ethics are so central to DeepMind’s corporate culture that a not insignificant number of its staff work in this field. And rightly so. Nick Bostrom, a Swedish philosopher who teaches at Oxford University, writes in his book Superintelligence, published in 2014, that artificial superintelligence could destroy humankind by prioritizing its specified simple goal above all else, including the human factor.

Nick Bostrom. University of Oxford, CC Attribution 4.0.

“In my opinion, it’s very appropriate that an organisation that has as its ambition to ‘solve intelligence’ has a process for thinking about what it would mean to succeed, even though it’s a long-term goal,” Bostrom said last year to the British newspaper The Guardian who asked him about the DeepMind Ethics Committee. “The creation of AI with the same powerful learning and planning abilities that make humans smart will be a watershed moment. When eventually we get there, it will raise a host of ethical and safety concerns that will need to be carefully addressed. It is good to start studying these in advance rather than leave all the preparation for the night before the exam.”

Another whistleblower, Stephen Hawking, told the BBC in 2014: “The development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race.” The following year, Microsoft founder Bill Gates voiced his concerns about the future of AI, saying he just didn’t understand how people could not worry about AI becoming so powerful that humans could no longer control it. This statement was directly at odds with one of the heads of Microsoft Research, Eric Horvitz, who said that he didn’t “fundamentally” believe that AI could become a threat. Bill Gates’s statement came on the heels of another talk, by Elon Musk, to a roomful of students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology: “I think we should be very careful about artificial intelligence. If I had to guess at what our biggest existential threat is, it’s probably that. So we need to be very careful,” he said, before adding, “With artificial intelligence we are summoning the demon.”

You don’t need to be an artificial intelligence skeptic to see the merits of setting safeguards around the research and use of this technology. DeepMind, in its wisdom, set up an ethics committee and contributes to research on artificial intelligence safety to ensure that the future of superintelligence is friendly, not hostile. After all, we don’t want to end up like David Bowman, arguing with a dysfunctional HAL 9000 about an important, if human concern: our survival.

As for any previous technologies that have led to disaster, the concern with AI is not so much the technology itself, but rather how it is used. Two dangers can spell destruction: nefarious intent (for example, creating a nuclear bomb to kill as many people as possible), and poor management (for example, the meltdown of the nuclear core at Chernobyl).

DeepMind has already looked into the problem of poor management, since machine learning accidents (benign or otherwise) are currently happening. Caused by design flaws and resulting in unintended and undesirable behaviours, some of these accidents are legendary. Remember Microsoft’s chatbot, which quickly became a virulent racist on Twitter? It had to be immediately shut down, causing much jeering on social and media networks.

Victoria Krakovna is a research scientist at DeepMind working on AI safety. Her personal blog features a master list of intelligent agents that indulged in unintended and undesirable behaviour; these incidents, while funny, give pause for thought. The list mostly features intelligent agents like DeepMind’s early creation, and video games. The video game fails are benign or beneficial, since they’re good for a laugh; but the same fails involving human health and safety would have dire consequences and raise questions of morality and ethics. These concerns need to be addressed now, given the advent of technologies like autonomous driving.

A truly fascinating occurrence of unanticipated AI behaviour is its “gaming” of the specified objective, generating a solution that satisfies the letter rather than the spirit of the stated objective. This is due to a poorly specified objective. One example in Krakovna’s master list involves the agent indefinitely pausing a game of Tetris to avoid losing. While the agent has indeed fulfilled the objective, i.e. not lose, neither can it be said to have won. In another gaming example, the agent found a creative solution to avoid being killed – crash the system. It seems agents are adept at finding and exploiting software bugs, performing actions that human intelligence would never have contemplated and, incidentally, revealing hidden design flaws. And did we mention the kamikaze agent that kills itself at the end of Level 1 in order to avoid losing at Level 2?

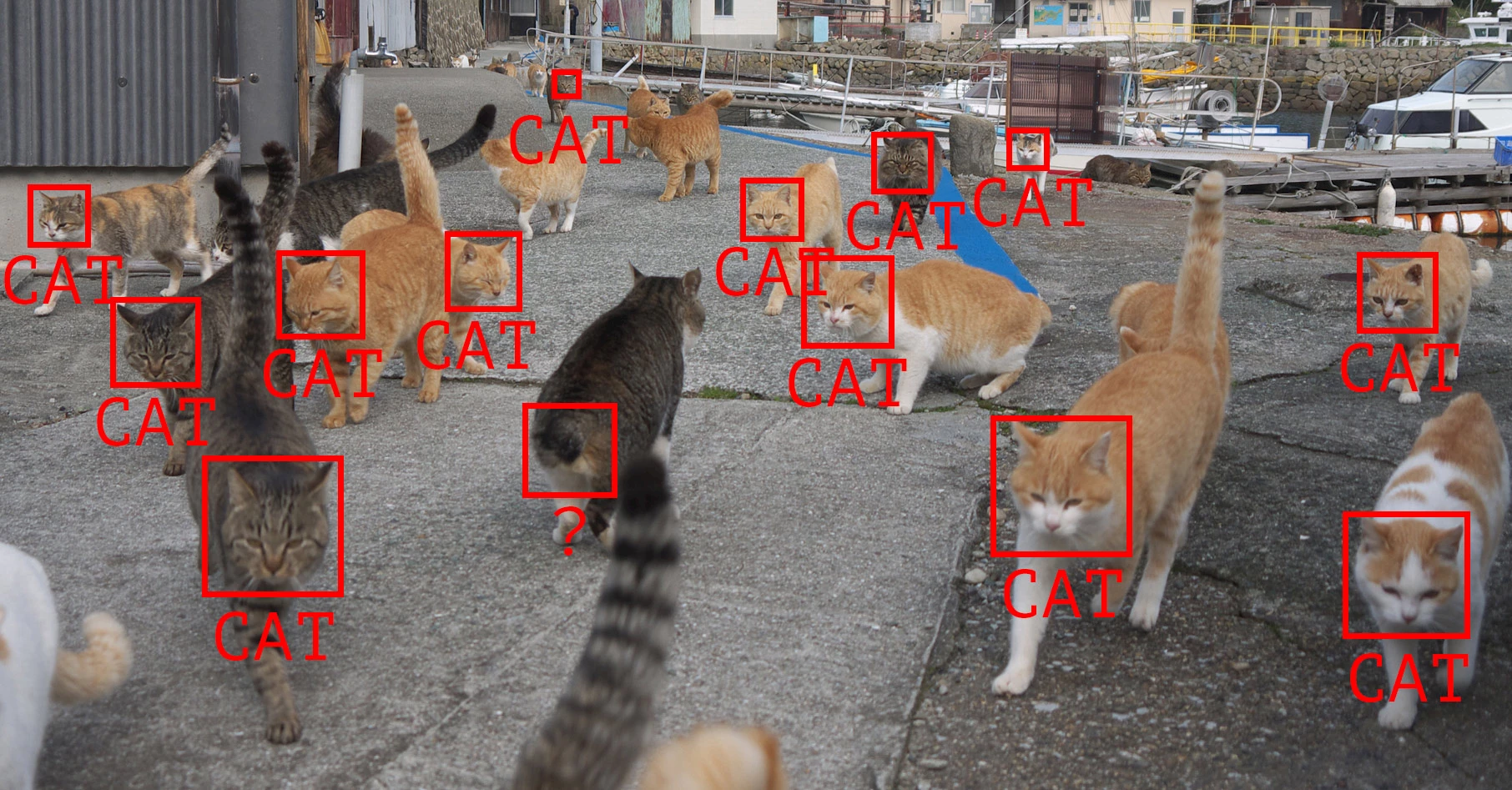

Cat recognition. © iStock.

Another interesting, unintended behaviour of AI is when an agent takes advantage of the way it is fed data, leading to “cheating”. For example, an AI trained to detect cancerous skin lesions learned that lesions photographed next to a ruler were more likely to be malignant. Another neural network trained to recognize edible and poisonous mushrooms took advantage of the fact that the edible/poisonous data was presented in alternating order, never actually learning any features of the actual mushrooms. The problem is that these systems are in fact designed to cheat, since they are programmed to provide results with as little work as possible. In other words, they are no different from human learners who conclude that the best way to get results without the work is to cheat. The difference is that machine learning systems are nothing more than evolved statistical classification systems with no concept of good, evil, or morality. In a humorous tweet, Joscha Bach, a researcher at the Harvard Program for Evolutionary Dynamics, coined the “Lebowski Theorem”, referring to the lazy hero in the Coen brothers film: “No superintelligent AI is going to bother with a task that is harder than hacking its reward function.”

Jeffrey “The Dude” Lebowski. © Working Title Films, Universal Pictures.

The more humans offload important functions to AI (beyond that of becoming a champion game player), the greater the risks. We can’t ignore high-profile whistleblowers; the dangers are real and identified. Science without conscience leads to a disaster with moral dimensions, and an excessive faith in technology is willful blindness. The problems associated with artificial intelligence stand at the crossroads of science, ethics and morality. Specialized companies like DeepMind are clear-sighted enough to consider the ramifications of their work, but other actors may not be so thoughtful, when they’re not downright malevolent. Not to mention the misuse of AI by nations, governments and radical groups for nefarious purposes. “Hacker” agents keep us endlessly entertained, but do raise the question of safety, which will become central to future developments in technology. Sooner or later, authorities and legislators will have to address the issue. Good thing that companies in this field, like DeepMind, are a step ahead, anticipating and incorporating issues of ethics in their practice.